The single, number-one thing that bothers me more than any other tendency in genealogy is what I call name creep: the tendency of a genealogical person to pick up names like a dog picks up fleas. Or, more accurately placing the blame, the tendency of genealogists to far too easily attach names to a person without proper support or documentation.

Let me give some examples. The most common form this takes — and the most annoying to me — is the attaching of a middle name or initial to a person when there is no evidence from primary sources that the person had a middle name or initial.

- Thomas Sparks becomes “Thomas Eli Sparks” or “Thomas Elijah Sparks” when there is no evidence at all in primary sources that he had or used a middle name. His wife, Rutha White, picks up the unexplained middle initial “B.“

- My ancestor William Bowdoin frequently becomes William B. Bowdoin in trees, when he never used a middle initial at all. (Worse still, he becomes a “Rev.”, and someone even put that, with the middle initial, on a recent replacement tombstone, when there’s no evidence at all he was a preacher.)

- Rebecca Hamilton becomes “Rebecca Elizabeth Hamilton” despite no record showing a middle initial. Her mother, Mary Kitchens, inexplicably becomes “Mary Susan Kitchens.”

Twenty-first century English-speaking people tend to assume middle names are a given, an expected part of any person’s name, when historically, middle names were not common for most Anglophiles until the mid to late nineteenth century. Prior to this, they were a feature that belonged mostly to royalty or the upper class, as a way to squeeze in more honors to more forebears. Gradually, more common people adopted the practice. For an obvious example, none of the first five U.S. presidents had a middle name, though all came from upper-class families: George Washington, John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe. But the sixth did, John Quincy Adams, with the middle name specifically given to honor Abigail Adams’ grandfather, John Quincy.

All of these presidents are well-documented historical figures. No one would think of attaching a middle name to Andrew Jackson without a clear source or a good reason, but I recently discovered that my ancestor Andrew Alldredge (born 1782) had apparently acquired the middle name Jackson, despite no one having heard of Andrew Jackson in 1782 (he did not become a celebrity until after the Battle of New Orleans in 1815).

Why do people do this? There are several main reasons, which I will go into. But the underlying motive, I think, is a genealogist’s drive for completeness, together with a tendency toward lumping, or perhaps a fear of splitting. A genealogist wants to have all the facts, and there’s no fact more personal than a person’s name. Not knowing a person’s middle name — and a modern person tends to assume that people had one — represents something unknown, a critical fact not filled in; and we leap at the opportunity to fill that in, and feel a sense of fulfillment when we do so. But the ultimate cause — as will be the culprit with most of the things that bother me — is a lack of discipline with sources.

Below I will outline several cases of name creep and why they happen; and then I’ll give some rules to follow to help you avoid it.

Conflation of people from different sources

One of the most common causes of name creep is conflation of people from different sources. By this I mean, you have several sources describing different events, and for whatever reason, you decide that they refer to the same person, and so conflate the people in the records, with different names, into one person with a combination of both names. And this is where it creeps: once you’ve conflated them, the combined name sticks to both people, and is handed down and becomes “traditional.”

Nathaniel “Benjamin” Aldridge

A case in point: in my work disentangling Nathan Alldredge and Nathaniel Aldridge, two men who lived around the same time and place and are often conflated, I was bugged by the “traditional” ascription to Nathaniel Aldridge of the name Nathaniel Benjamin Aldridge — despite the evident fact that he never used even a middle initial in records. Digging into the historiography, I found this, which I excerpt from Franklin Rudolph Aldridge, one of the main sources for this family:

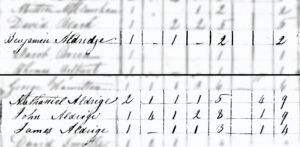

Nathaniel Aldridge appears to have removed to [Ninety-Six District,] South Carolina, [where he had land grants in 1786 and 1798 and appeared on the 1790 census.] One Benjamin Aldridge also had two land grants in the Ninety-Six district, [one in] 1785 and the other the exact date as Nathaniel, 5th February 1798. No Benjamin is found in the 1790 census for this district and we may assume that Nathaniel and Benjamin are the same person, however this is not conclusive. An interview with a descendant of this family says the full name was Nathaniel Benjamin. This may be the answer for the absent Benjamin in 1790 census.

Franklin Rudolph Aldridge, Aldridge Records, vol. 2 (Nashville: self-published, 1975), 58–59 ([Ancestry], [FamilySearch])

Why would we assume that Nathaniel and Benjamin are the same person? What sane person would take out two legal documents, important grants of government land, in two different names on the same day? Would that not just be asking for legal problems? “[A descendant] says the full name was Nathaniel Benjamin.” Well, yes. By 1975, someone else had made the same mistake and handed it down as if it were fact.

So for all time since, in a multiplicity of family trees, Nathaniel Aldridge has assumed the name Nathaniel Benjamin Aldridge. And the name, by continued creep, is handed down to his son, Nathaniel Aldridge Jr. (becoming Nathaniel Benjamin Aldridge Jr.), who again never used a middle initial in any record. And because of this conflation, any future source we might encounter referring to Benjamin Aldridge is likewise assumed to refer to the same man as Nathaniel — leading to more and more creeping conflation.

A majority of online trees identify the wife of Nathaniel “Benjamin” Aldridge Jr. as Jane Armstrong or Jane Brandon Armstrong, despite the woman never appearing in any record (she died about 1845). But even a glancing examination reveals this to be a case of continued name creep.

- F. R. Aldridge again reported, “The wife of Nathaniel Aldridge, Junior is said to have been an Armstrong, however this may not be true” (Aldridge Records II, 60).

- The 1820 state census of Lawrence County, Alabama, lists separate men named Benjamin Aldridge, Nathaniel Aldridge, John Aldridge, and James Aldridge (Ancestry).

- Benjamin Aldridge died about 1827, leaving a widow, Jane. Nathaniel Aldridge and wife continued to be listed on the 1830 census.

Because of name creep — because of the conflation of Nathaniel Aldridge with Benjamin Aldridge — the unknown wife of Nathaniel Aldridge Jr., previously “said to have been an Armstrong,” becomes Jane Armstrong in people’s families histories, despite there being no evidence at all that Nathaniel Aldridge’s wife was named Jane.

But this story doesn’t stop even there.

I don’t know who or how, but somebody discovered a James Armstrong who settled in Rowan County, North Carolina (where, I might point out, Nathaniel Aldridge never lived), who had a daughter named Jane. Jane either married a Brandon, or had the middle name Brandon — both claims appear equally unsourced — but it appears to be because of this that “Jane Armstrong,” wife of Nathaniel “Benjamin” Aldridge, acquired the full name Jane Brandon Armstrong. Jane, daughter of James Armstrong, actually married Ninian Steele and moved to Indiana, and never lived in Alabama at all — but that didn’t stop sloppy researchers from linking her Find a Grave memorial as a supporting source for “Jane” Aldridge. I blame Ancestry’s “hint” algorithm for this particularly extreme creep, which conflates similarly named people and pushes the conflation on unsuspecting novices — but I blame genealogists for not exercising the critical thinking to determine that two people with similar names and dates, in different places, married to different men, are not the same person.

Tacking on information from questionable sources

This second case is perhaps also a novice error, one again related to lack of discipline with sources: not distinguishing between the quality of sources.

Rebecca (Hamilton) Dutton-Williams

In the case I mentioned above of Rebecca Hamilton, who picks up the middle name “Elizabeth,” despite no primary source which shows her to have a middle initial, I finally discovered today, I think, the source of the extra name.

Out of all the dozen sources linked to her profile on FamilySearch, each source gives her name as Rebecca or Becky, no middle name or initial — except one: the 1938 death record of her oldest son, William Harvey Williams, which gives his parents’ names as Augustus Williams and Elizabeth Hamilton.

Do you see the problem? Rebecca (Hamilton) Williams died in 1908, thirty years before this record. By the time this death certificate was written, Harvey Williams, her son, was also dead, at age seventy. Whoever was filling out the form, probably a child or grandchild, may never have known Harvey’s mother at all. Though a death certificate is a primary source for a person’s death, it is not a primary source for the names of his parents. Obviously, the informant couldn’t remember his mother’s name and made a mistake.

So the researcher needs to critically weigh the quality of the sources. If ten sources created during Rebecca’s life, primary sources, all give her name as only Rebecca, and one record, created thirty years after she died, gives her name as Elizabeth, what should we do? No, we shouldn’t tack on an extra name from the questionable source. And a secondary source that conflicts with numerous primary sources is decidedly a questionable source.

George Lewis

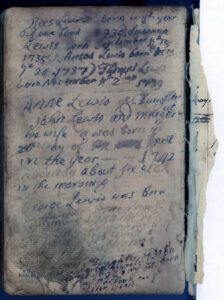

A similar case: I found my ancestor George Lewis (born 1744), identified on Find a Grave and WikiTree and oh, FamilySearch too, as George Shellie Lewis. But the man’s name and birthdate are written in his father’s 1727 Welsh Bible, as only “George Lewis.” You can’t really get more authoritative than that. No primary source for George Lewis (and there are surprisingly many, including his will) uses the name Shellie or shows even a middle initial. So what’s the source of this tacked-on extra name? It turns out, Thomas M. Owen‘s 1920 History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography, published more than a century after George Lewis died. In a biographical sketch of Lorenzo Dow Lewis, a great-grandson of George Lewis and a Presbyterian minister, Owen wrote that L. D. “was the son of Chrisman Lewis; grandson of Gabriel Lewis; great-grandson of Shellie Lewis; great-great-grandson of George Lewis . . . “

This is wrong. L. D. Lewis was the great-grandson of George Lewis; the great-great-grandson of John Lewis. The Owen biography — not written from primary sources at all, but from self-submitted family information — incorrectly names L. D.’s great-grandfather, inserting an extra generation into the tree. L. D. Lewis — born forty years after his great-grandfather died; six years after his grandfather died; and even his father was born after his own grandfather died — born 150 miles from the county where George Lewis lived and died — wrote his ancestry entirely from remembered family hearsay, and very clearly got it wrong. And yet for some reason, genealogists today take this poorly-sourced hearsay as an authoritative source. Is it because it says “Owen” on the cover?

No, sometimes I think it’s simply poor critical thinking, poor evaluation of sources and facts, maybe even wishful thinking and an eagerness to add something novel and unknown to the family tree, even if it makes no sense and contradicts every other source we have. I challenged the man on WikiTree who kept changing George Lewis’s name to add Shellie, to show his source and explain his reasoning, and he rationalized:

There is a problematic source for the name “Shellie”. … George Shellie Lewis has been bifurcated into Shellie and George Lewis. [Owen and Owen] go on to state, incorrectly, in conformity with the popular three brothers founding myth, “[he] came with his two brothers, Amos and Mordecai, to the United States from Wales in 1794.” Their source, quite possibly Dow Lewis himself, became sketchy about his more remote ancestors; but we have “Shellie” in the correct genealogical slot in a source dated 1921. This makes it likely, but unproven, that Dow Lewis’ great-grandfather did bear the name “Shellie”.

The “correct genealogical slot”? What exactly is correct about naming an ancestor who never existed? Openly admitting that this account is incorrect on several different points and based on disproven myth in another, what exactly makes anything about this source “likely”?

Other people’s family trees

Caution about questionable sources goes double for other people’s family trees. It is one thing if a person consistently used a middle initial in life, and you find a family tree that spells out what the middle name was. I still would like to see a primary source for the middle name, but especially for families that are only ancillary to my research, I sometimes let that slide, and incorporate a middle name someone else reported in their family tree without an identified source. It is another thing entirely to tack on additional names to somebody who never even used a middle initial, simply because somebody else has it in their unsourced tree.

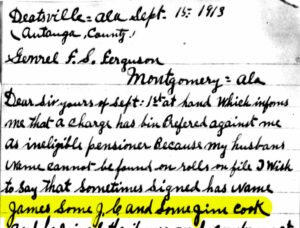

Documenting names not shown in primary sources

And “personal knowledge” or “family tradition.” Yes, especially when I was first getting started in research, I sometimes took for granted that names have to have sources too. My great-grandfather James Council Cook never used a middle initial in any record that I know of; it was always James Cook, in thirty-something primary sources currently linked on FamilySearch. So how do I know he had a middle name? Though he never used a middle initial, people who knew him fairly consistently used the middle initial C for him after his death, in the death certificates of his children and in correspondence about his Confederate service, for example. My grandmother said that her father, Joe Cook, always gave his father’s name as James Council Cook. I have documentation of Joe Cook writing his father’s name as J. C. Cook, and of my grandmother writing down the full name James Council Cook as early as the 1960s, when her father was still alive. So all of this constitutes a clear documentation of the family tradition: who said his middle initial was C, who said his middle name was Council, and when. When a name isn’t spelled out by primary sources, this is the kind of documentation that needs to happen.

You may know from “personal knowledge” what your ancestors’ middle names were, but in transmitting that knowledge to other people, if you can’t document how you know what you know, that knowledge becomes a questionable source. Even if you add only a note that “my grandmother told me this was his middle name,” you need to be able to answer the question, “How do I know this was my ancestor’s middle name?” If the answer to that question is, “I don’t know,” or, “I found it in someone else’s family tree,” you need to critically examine the fact.

Questionable assumptions, hasty conclusions, and normalization

I will shoehorn several other, related cases into this last category.

Assuming middle names

Don’t assume anything. Just because Andrew Alldredge (born 1782) had a grandson named Andrew Jackson Alldredge (born 1829), doesn’t mean the grandfather was also named Andrew Jackson. The latter was clearly named both for his grandfather and the war hero turned presidential candidate; the former had no such namesake.

On a related note, though people named Andrew J., born between 1828 and 1845, were usually named Andrew Jackson; and people named George W., born throughout the nineteenth century, were more often than not named George Washington, it’s unwise to jump to those conclusions. As soon as you do, it will creep away from you.

Especially don’t assume that if a child had a particular middle name, the father must also have had that same middle name. Stephen Penn had a son named Stephen Chandler Penn, and I often find people referring to the father as Stephen Chandler Penn Sr. and the son Stephen Chandler Penn Jr. — but there’s no evidence at all in primary sources that Stephen Penn, the father, had a middle name. Similarly, if there’s a long string of men named Notley Dutton, with some of them eventually named Notley Thomas Dutton and clearly using the middle initial T, that’s not evidence that all of them were named Notley Thomas Dutton.

Generational suffixes

Don’t tack on generational titles like “Jr.”, “Sr.”, “III”, and so on, as if they were a part of a person’s name, without support from sources. If there is a long string of ancestors of the same name, you may find such suffixes helpful in your family tree for distinguishing between them, but unless they were a formal part of the person’s name — and such particles seldom were, prior to the nineteenth century, except for with royalty or the very upper class — they don’t belong in the name field, especially not in shared trees. The name field is for the name the subject knew and used for themselves in his or her lifetime.

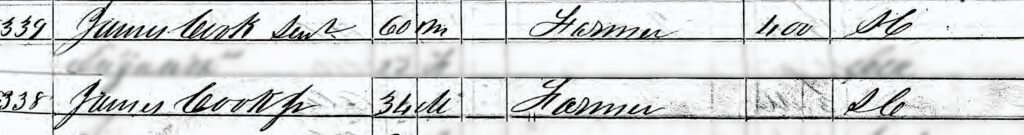

Suffixes like junior (Latin “younger”) and senior (Latin “older”) were not typically a formal part of a person’s name, but were used descriptively and relationally to tell people of the same name apart in records. If there are two people listed near each other on the census in a nineteenth century census report, and one is “Junior” and the other “Senior” — that’s not a part of their names. The census enumerator applied such terms simply to say, for example, that one man named “James Cook” was the older one and the other was the younger one. In the famous case of my ancestor James Cook on the 1850 census, when he was listed as “James Cook Jr.” and his next-door neighbor listed as “James Cook Sr.”, many have concluded (including we, at one time) that the two men were father and son, but they definitely weren’t — they were probably uncle and nephew.

By attaching a suffix to a name that wasn’t a part of the name, formally and of record, you are projecting your assumptions on the situation. By applying those labels, you may be assuming, as in the case of my ancestor Nicholas Aldridge, that one man is the son of another man who may or may not be related. Currently on the FamilySearch tree, Nicholas Aldridge is named Nicholas Aldridge IV, based on the unproven assumption that a 1653 Hampshire baptism record belongs to him, showing a Nicholas baptized in 1653, the son of another Nicholas. The tree identifies the older Nicholas, the one in Hampshire, as Nicholas Aldridge III; but I’ve seen no proof of the connection at all, just the happenstance of a Nicholas Aldridge born around the time we expect our Nicholas Aldridge was born. The lack of support beyond the coincidence of names is one problem; the attachment of these suffixes, “III” and “IV”, creates another. Neither of these two men, even if they were related, used or would have understood these suffixes; but a novice unfamiliar with the situation and sources might take the suffixes themselves as “proof”.

Sometimes, the suffixes “Jr.” and “Sr.” were used informally, even in family records, to distinguish between “younger” and “older” family members, without that being a formal part of their name, especially when it was common to refer to men by their initials. My great-grandfather, William Walter Aldridge, was often referred to in records as “W. W. Aldridge Jr.,” and his father, William Warren Aldridge, as “W. W. Aldridge Sr.,” when clearly they had different names and one was not, formally, a “Jr.” of the other. I found a case just recently where a cousin, Robert Elmore Brown, son of Robert Ernest Brown, was called “Junior” as a nickname his whole life, because he and his father were both Robert E. His tombstone bears the name Robert E. Brown Jr., even though the “Jr.” was never formally part of his name.

It shouldn’t need to be said that you shouldn’t attach maiden names to people in a shared tree if you aren’t completely sure. Don’t post unproven data without good documentation or a good explanation.

Normalization

Finally, don’t normalize. Your norms today are not necessarily your ancestors’ norms. And nobody is really normal. By normalize, I mean:

- Don’t expand nicknames without good evidence. If he always went by “James Willie” and spelled that out in official documents, who are we to change it to “James William”?

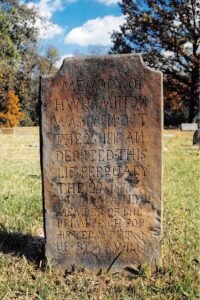

- Don’t change names found in records because a different name “sounds better” to you. “Harvey William” may sound awkward and unaesthetic to our ears, but if he always used the initials “H. W.” and had that placed on his tombstone, then that’s the order the names should be in.

- Don’t assume a standardized spelling. If a person consistently used a particular spelling of their name, even if you find it unconventional or incorrect — “misspelling” a traditional name, for example; McCager instead of Micajah — we should respect the person’s spelling, as recorded in the sources. In the past, I’ve been particularly guilty of this one — with women named “Francis,” for example, changing it to “Frances” (that’s the way the girl’s name is spelled); or dropping the r southerners sometimes add to their names because that’s the way they say it (clearly, with Louellar, they were trying to spell the name Louella). It’s easy to judge others in the past, assume they were incompetent or couldn’t spell their own name or didn’t know better — but all of this is a form of presentism.*

* Of course, we also have to consider the case that some people actually couldn’t spell. If the person really was demonstrably illiterate, or if the only sources we have are of someone else spelling their name for them, I do allow myself some leeway with the spelling (after all, I know them better than some random census taker). But where we have primary sources, actually written by the person or someone close to them, we should follow that where possible and appropriate.

Rules for avoiding name creep

Here are a few rules for avoiding name creep that I hope will be helpful.

- Don’t attach a middle name or middle initial to a person unless you have a primary source that shows the person at least used a middle initial.

- Don’t assume two records with different names refer to the same person, without very clear evidence from other sources that the second name could have belonged to the same person (e.g. you can show that the person at least had a middle initial).

- Do evaluate your sources. Not every source is a primary source. Not every source is valid and credible. Not every source warrants adding information to your tree.

- Don’t add an extra name to a person from a single source that contradicts every other primary source. Add a note, “This record says this.”

- Don’t add additional, unsupported names from someone else’s unsourced family tree.

- Do add support for names to your own tree, explaining how you know this was a person’s name, if the records don’t spell it out.

- Don’t attach generational suffixes to a name unless you have primary sources showing the person, or their close family members, used that prefix as a formal part of their name.

- Don’t attach a maiden name to a person in a shared tree based on a speculation, guess, or another unsourced tree. Only do so if you have sources that show the name. Post speculations, theories, and guesses as notes.

- Don’t assume you know a person’s middle name, or assume a person had a middle name.

- Don’t normalize a person’s name, based on your judgment of propriety, correctness, or aesthetics.

I’ve seen a family with 3 generations of the exact same male name. The Birth Certificate for the middle generation actually includes the suffix Jr. But when that person grew up and had a son with the same name, he started using the suffix Sr.!

My grandmother, Jessie Margaret (Rawley) Boylan (1882 – 1965), after getting married, usually signed her name as Jessie R. Boylan, Jessie Rawley Boylan, or Mrs. Thomas Boylan, Sr. Her only child was Thomas Michael Boylan, Jr., and he has a son, Thomas Boylan, III.

https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Rawley-95

I’ve seen many cases, often in obituaries, where all of the married daughters have the same initial as a middle name, and it matches the start of their maiden name.

My middle name, Francis, isn’t on my Birth Certificate, because it’s my Catholic Confirmation name, at age 6 and 10 month.

Excellent advice! I’ve seen examples of all of these types of name creep, and they drive me nuts. In the most annoying recent example, I submitted a DAR application for a prospective member who had an ancestor named “Susie Anna ____.” This form of the name (or “Susie A.”) was used on her birth and marriage records and some censuses, with “Susan” showing up only on other censuses, her obituary (written after her husband had also died), and a child’s death certificate. The DAR genealogist changed it to “Susan Anna,” because, as she informed us, “Susie is a nickname for Susan.” This was especially ironic, since my own name is Susan (and I go by Susie)! I remain convinced that this woman’s name was Susie Anna, not Susan Anna!

As the III of my name I’m very aware of the issues. I would point to ‘Emily Post’ on manners and usage. At least in my family it was a ‘standard’. Per most books on the subject the designation was not to be used at ALL times. From 1950 (my birth) to 1968 (my parent’s move east) we all lived in Chicago. During those 18 years I always used III. BUT in ’68 when my parents left town ‘manners’ dictated I used Jr to avoid confusion. When my grandfather died (1972) ‘manners’ dictated I was to use Sr. if I chose to use anything. I moved east near my parents and, yet again, became Jr. Official records were even more complicated. IL DOT wouldn’t include any differentiation. In 1998 I actually had an issue over a speeding ticket my grandfather had received in 1962! When I registered for the draft I couldn’t use III but when I got my passport I HAD to use III as it appeared on my birth certificate. I could go on but you get my drift.

I didn’t know any of this and never gave it a thought. This was so helpful to know about. When ancestry ran the hints related to your ancestors I thought this was 100 percent right. Never questioned it. Thank you for an eye opener.

Hi, thanks for the comment. No, Ancestry’s “hints” are absolutely not always right. Ancestry’s “hints” are based on a very dumb and simple algorithm that looks for whether the names and dates of someone you entered in your tree are similar to the names and dates of a person someone else entered. It has no logic to discern whether the suggestion even makes sense. It does people a great disservice in not making it more clear that this is just a “possible ancestor”. It is up to you and other researchers to examine what it shows you — and they don’t even make that very easy — and determine whether it does make sense and whether there are records that support it.

I share the same pet peeve. Name Creep must end. This post is so well written and so chock full of great information. Thank you for writing it!