The second part in a two-part series. (Part 1.)

This article is distilled from a longer research paper, which is shared below: “Connecting William Bowdoin, Part 2: Discovering the Relationship of William Bowdoin (b. 1802) of Autauga County, Alabama, to the Family of William Bowdoin (b. ca. 1740) through Machine Learning DNA Analysis”

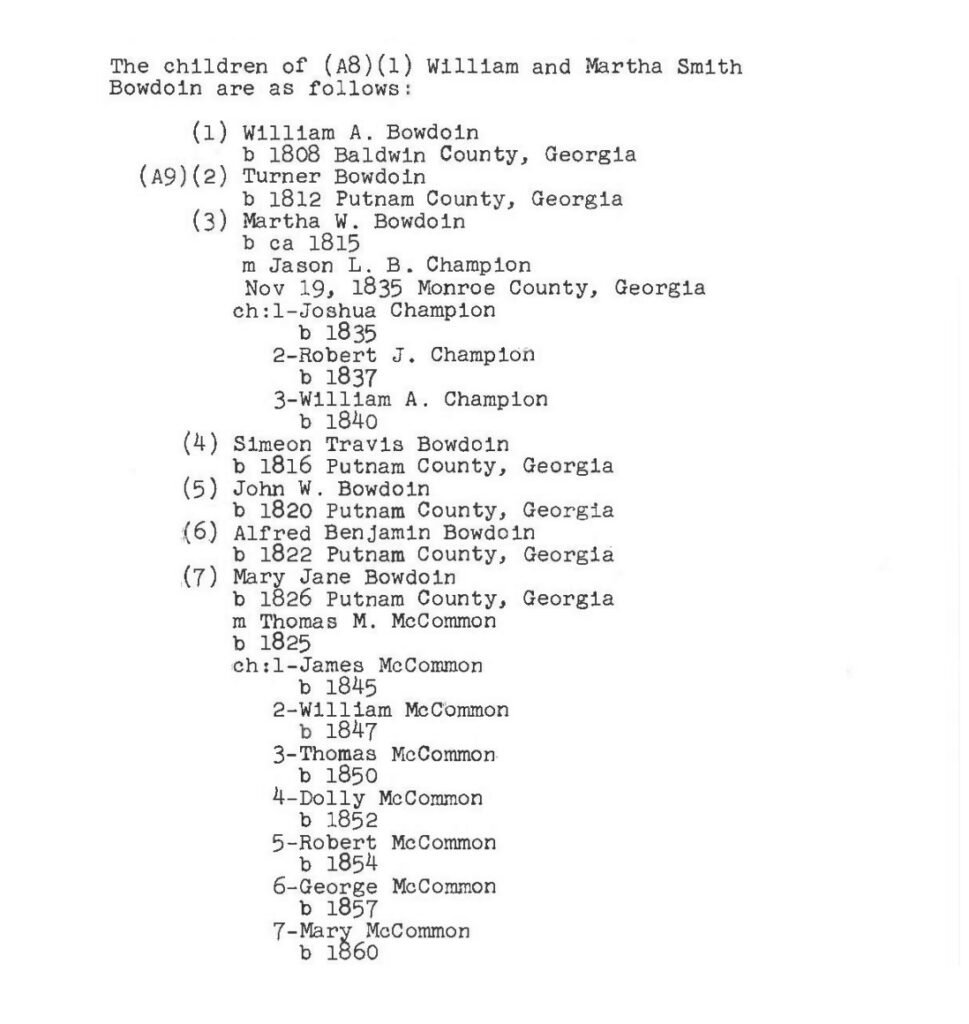

In the last post, I reexamined common assumptions about my ancestor, William Bowdoin (b. 1802) of Autauga County, Alabama, and using Y-DNA and preliminary findings from autosomal DNA, I picked up the trail that led to a connection between him and the family of William Bowdoin (b. ca. 1740) of Randolph County, North Carolina, who was almost certainly my William’s grandfather. Using an examination of primary sources and a process of elimination, I narrowed down the candidates for my William’s father to one likely candidate, Josiah Bowdoin (b. ca. 1780).

But can a connection from William to Josiah be proved? I have discovered no records that indicate definitely that Josiah Bowdoin was my William’s father. In this post, I turn to a deep DNA analysis using traditional DNA matching and clustering as well as Machine Learning techniques and algorithms, to search for scientific evidence of my ancestor’s connections. In the end, I discovered even more than I set out to find: I found evidence not only that William Bowdoin (b. 1802)’s father was Josiah Bowdoin (b. 1780), but that his mother was an unknown Ms. Read, daughter of Arthur Read and Martha Spinks.

A ground for searching: Ancestry’s Pro Tools

I began this study in part as an experiment to see what I could do with Ancestry’s Pro Tools. With regard to DNA, the main feature the Pro Tools offers is the ability to view the match value of shared matches’ matches with each other. I subscribed to the Pro Tools solely for this, and while I think it is overpriced, it is indeed a “game changer.”

The implications didn’t occur to me immediately, but as soon as I began this Bowdoin project I realized: I could do a level of clustering before not possible. In the past, tools like Jonathan Brecher’s Shared Clustering tool allowed us to cluster Ancestry matches by hierarchical clustering, but only by appearance, that is, a binary 1 or 0, whether a match is present in another match’s shared matches or not. With this, I could do an actual distance-based clustering: use the shared cM values of matches with each other as a distance measure for input into a clustering algorithm.

There was the plus, too, of Ancestry’s large matching base, so much larger than any other service, with numbers (25 million users tested as of 2023) approaching a true sample of the U.S. population, giving a high likelihood that I would find matches. Ancestry also has downsides, of course. It is severely disabled in its lack of a chromosome browser: If AncestryDNA had a chromosome browser, I could have answered these questions years ago. And the prohibition of any downloading of match data meant that I had to invest hundreds of hours into manually copying shared matches into a spreadsheet.

In total, I created a 925-squared matrix, with 924 individuals who match my grandfather, Robert P. Richardson (“R.P.R.”) in some relation to the Bowdoin family and their match values with him and with each other. They do not all match each other, but most match at least a dozen or so other people in the matrix; some, as many as a hundred or more. The only person who matches all of them is my grandfather. In sum, there are 23,150 pairwise match values.

Group matching

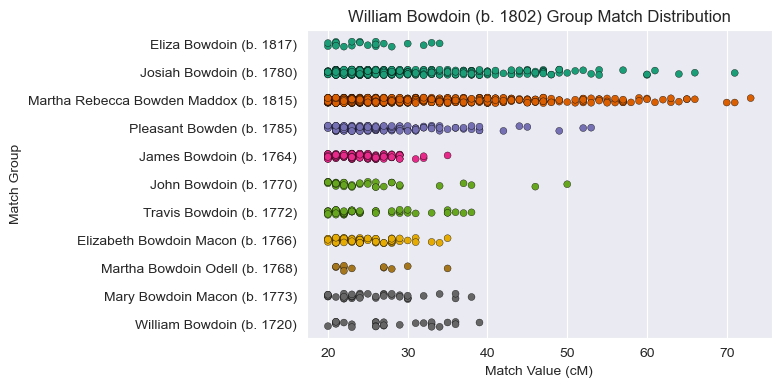

I tooled and experimented quite a bit, trying to determine the best methods and algorithms for harnessing this data. In the end, one of the most effective methods was surprisingly simple: group matching. By this I mean, grouping matches by their common ancestor, and then comparing each group’s matches with each other group. It works, in principle, because each group is a large cluster and all are subgroups of the same supercluster. Since I already know from the beginning that every member of each group descends from the same common ancestor, and every member of every group descends from William Bowdoin (b. 1740), I can abstract away the smaller clusters. Concentrating on group matching smooths out the irregularities of individual matching—some people having unusually large matches; others having unusually small matches—and shows whether, on average, one group is closer to another group.

On the individual level, many if not most individuals in the groups show the same trends that are evident in the group matching. I considered showing a series of individual case studies, but realized quickly into writing the first couple that each case study would show read exactly the same way as my grandfather’s: “After his closest cousins, R.P.R.’s largest and most numerous matches are to descendants of Josiah Bowdoin and also of Martha Rebecca (Bowden) Maddox.” The people whose results were different were averaged out by the overwhelming majority of people whose results were the same. And though simple, this is a basic Machine Learning algorithm in itself.

I grouped the matches into these groups—shown with R.P.R.’s highest match to the group and the average of R.P.R.’s matches with all members of the groups.*

* These figures are after I discarded a small number of outliers. In the William Bowdoin (b. 1802) group, the highest match and average match include only his matches with descendants of William other than R.P.R.’s ancestor, Reddin Read Bowdoin, since his matches to his closer cousins are much larger than the average.

R.P.R. Matches with Each Match Group

| Match group (descendants of) | # Matches | Highest match | Average match |

|---|---|---|---|

| William Bowdoin (b. 1802) | 134 | 77 cM | 27.4 cM |

| Eliza Bowdoin (b. 1817) | 13 | 32 cM | 13.5 cM |

| Martha Rebecca Bowden Maddox (b. 1815) | 128 | 59 cM | 19.8 cM |

| Josiah Bowdoin (b. 1780) | 108 | 61 cM | 19.4 cM |

| Pleasant Bowden (b. 1785) | 80 | 26 cM | 14.0 cM |

| James Bowdoin (b. 1764) | 74 | 28 cM | 15.1 cM |

| John Bowdon (b. 1770) | 15 | 23 cM | 15.0 cM |

| Travis Bowdoin (b. 1772) | 52 | 30 cM | 14.1 cM |

| Elizabeth Bowdoin Macon (b. 1766) | 38 | 36 cM | 16.3 cM |

| Martha Bowdoin Odell (b. 1768) | 13 | 21 cM | 13.7 cM |

| Mary Bowdoin Macon (b. 1773) | 30 | 34 cM | 16.5 cM |

| William Bowdon (b. 1720) | 19 | 34 cM | 13.1 cM |

Notice that even considering Robert’s matches by himself, Josiah Bowdoin takes a lead. His group has an high match about twice that of his brothers, and an average match 4 to 5 cM highest overall.

- Matches from descendants from Eliza Bowdoin, William (b. 1802)’s sister, were disappointingly distant, but not outside the predicted range. (More on this in the paper.)

- Elizabeth Bowden Macon’s group has some definite-but-not-fully-explained endogamy with the Josiah Bowdoin group.

William Bowdoin (b. 1802) matching as a group

If there were any question at all whether William Bowdoin (b. 1802) in fact descended from William Bowdoin (b. 1740), examining the combined DNA matches of William (b. 1802)’s descendants with the children of William (b. 1740) quickly dispels it. 78.5% (106 out of 135) of William (b. 1802)’s descendants matched at least one descendant of William (b. 1740) with a value of 20 cM or larger; 48.9% (66 out of 135) matched at least five descendants.

WIlliam Bowdoin (b. 1802) Group Matches with Other Match Groups

| Match group (descendants of) | # who match at least one | Total matches | Highest match | Average match |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eliza Bowdoin (b. 1817) | 14 (10.4%) | 31 | 34 cM | 20.3 cM |

| Martha Rebecca Bowden Maddox | 110 (81.5%) | 1076 | 73 cM | 27.8 cM |

| Josiah Bowdoin (b. 1780) | 86 (63.7%) | 517 | 71 cM | 26.4 cM |

| Pleasant Bowden (b. 1785) | 43 (31.9%) | 232 | 53 cM | 22.6 cM |

| James Bowdoin (b. 1764) | 69 (51.1%) | 243 | 35 cM | 20.9 cM |

| John Bowdon (b. 1770) | 25 (18.5%) | 46 | 50 cM | 21.7 cM |

| Travis Bowdoin (b. 1772) | 26 (19.3%) | 97 | 38 cM | 19.1 cM |

| Elizabeth Bowdoin Macon (b. 1766) | 31 (23.0%) | 112 | 35 cM | 21.3 cM |

| Martha Bowdoin Odell (b. 1768) | 10 (7.4%) | 22 | 35 cM | 18.8 cM |

| Mary Bowdoin Macon (b. 1773) | 19 (14.1%) | 71 | 38 cM | 21.3 cM |

| William Bowdon (b. 1720) | 14 (10.4%) | 46 | 39 cM | 20.6 cM |

Here we see the clear dominance of Josiah Bowdoin in the combined matches of William Bowdoin (b. 1802), versus any other son of William Bowdoin (b. 1740). The only one who even begins to hold a candle is Pleasant. For reasons not yet explained, Pleasant Bowden’s descendants have a higher degree of matching with William (b. 1802) than his brothers besides Josiah. Could Pleasant’s wife have been kin to Josiah’s wife?

And Martha Rebecca. If you haven’t read my papers yet, you may be in the dark. I had no idea, either.

Martha Rebecca (Bowden) Maddox

When I first began digging into my grandfather’s matches, I was bowled over by the overwhelming number of matches to Martha Rebecca (Bowden) Maddox (b. 1815). He has hundreds of matches to her descendants, and close matches, in the top tier, alongside and above matches to Josiah Bowdoin descendants. And this didn’t make sense, because according to the trees of nearly everybody, Martha Rebecca was a descendant of James Bowdoin (b. 1764) > William Bowdoin (b. 1786).

As the overall evidence seemed to tip more and more in favor of Josiah, I was more and more perturbed by these excessive matches to Martha Rebecca. Not only did R.P.R. have them, but every descendant of William and also of Josiah had numerous and strong matches to Martha Rebecca’s descendants. And with her having had fifteen children, and those fifteen children going on to also “be fruitful and multiply”, I do mean numerous.

I didn’t know how to explain this. William (b. 1802)’s descendants did not have close matches with other descendants of James Bowdoin (b. 1764). And the more matches I catalogued, the more I realized—neither did Martha Rebecca’s. Martha Rebecca Bowden’s close matches were with Josiah Bowden’s descendants and William Bowdoin (b. 1802)’s descendants, not with either James (b. 1764) or William (b. 1786).

Martha Rebecca Bowden Group Matches with Other Match Groups

| Match group (descendants of) | # who match at least one | Total matches | Highest match | Weighted average match |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| William Bowdoin (b. 1802) | 128 (100%) | 1076 | 104 cM | 31.7 cM |

| Eliza Bowdoin (b. 1817) | 24 (18.9%) | 34 | 41 cM | 25.3 cM |

| Josiah Bowdoin (b. 1780) | 117 (91.4%) | 1034 | 126 cM | 36.3 cM |

| William Bowdoin (b. 1786) | 94 (73.4%) | 317 | 64 cM | 34.6 cM |

| James Bowdoin (b. 1764) (other branches) | 38 (47.7%) | 223 | 73 cM | 35.5 cM |

| Pleasant Bowdoin (b. 1785) | 93 (72.7%) | 614 | 78 cM | 32.8 cM |

| John Bowdon (b. 1770) | 38 (29.7%) | 57 | 52 cM | 28.4 cM |

| Travis Bowdoin (b. 1772) | 43 (33.6%) | 125 | 60 cM | 34.0 cM |

| Elizabeth Bowdoin Macon (b. 1766) | 48 (37.5%) | 130 | 51 cM | 31.7 cM |

| Martha Bowdoin Odell (b. 1768) | 18 (14.1%) | 34 | 39 cM | 26.6 cM |

| Mary Bowdoin Macon (b. 1773) | 55 (43.0)% | 125 | 42 cM | 30.3 cM |

| William Bowdon (b. 1720) | 35 (27.2%) | 65 | 46 cM | 33.0 cM |

For several reasons, I had to use a weighted match average for Martha Rebecca’s grouped descendants, and for the same reasons, had to use a violin plot instead of a strip plot to show their distribution. See more details in the paper.

Compared even with William Bowdoin (b. 1786), Martha Rebecca Bowden’s descendants have an astounding number and strength of matches with both William Bowdoin (b. 1802) and Josiah Bowdoin—showing a clear affinity with both groups.

Something was clearly not right. Martha Rebecca Bowden’s matches were simply too high and too numerous. I found myself asking repeatedly if people’s trees were right. And then, I found Martha Rebecca in the Read and Spinks matches too, and I knew something was wrong.

U. Bowdoin Marsh, author of the 1982 book on the Coffee County Bowdoin family—of which Martha Rebecca Bowden was a part—was likewise a descendant of William Bowdoin (b. 1786). Surely, I thought, he would have researched the question. But no. Bowdoin Marsh did not include Martha Rebecca (Bowden) Maddox in his list of the children of William Bowdoin (b. 1786). She wasn’t even in the book.

William Bowdoin (b. 1786) had another daughter named Martha who was born in 1814, Martha W. Maddox. Why would he have named another daughter Martha the very next year?

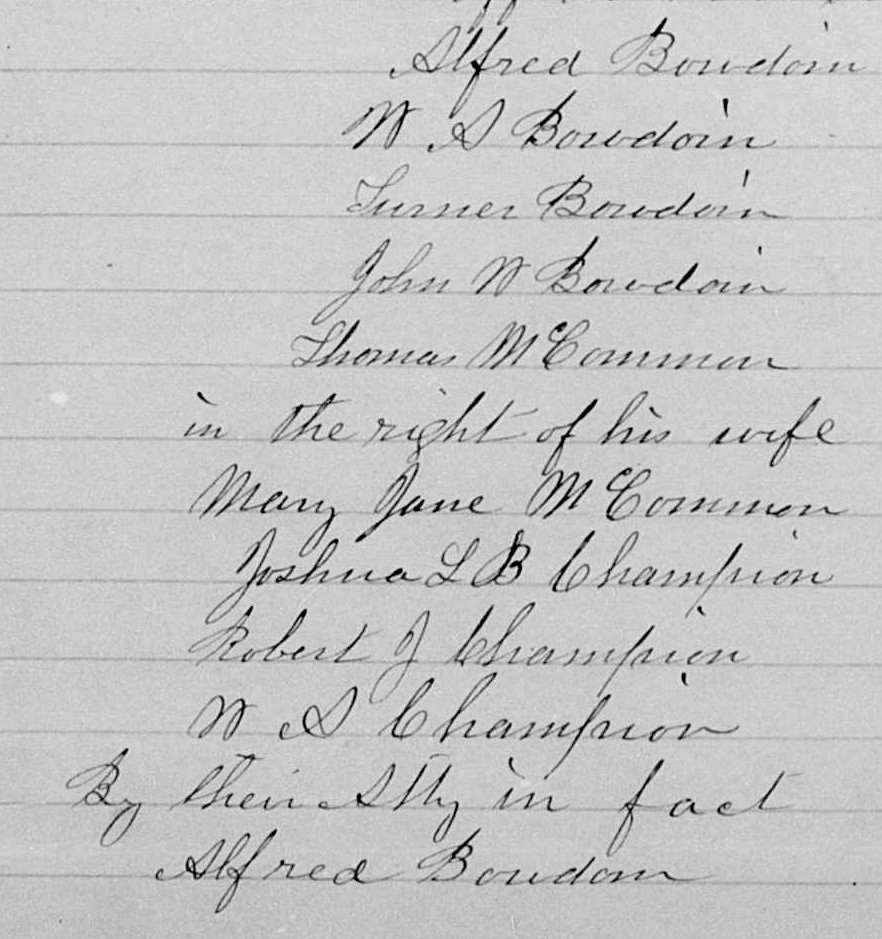

William Bowdoin (b. 1786) died in about 1865. In 1866, his surviving children and heirs needed to sell some inherited land to their brother, so they jointly made a deed to him. Martha Rebecca (Bowden) Maddox was not listed those heirs. She was not a daughter of William Bowdoin (b. 1786).

So who was she?

The discovery of the Read-Spinks connection—and the fact that Martha Rebecca clearly shared it too—is what finally tied everything together. Martha Rebecca had higher matches to William (b. 1802) than anyone else because she was a closer relative than anyone else. She was his sister, too.

Read and Spinks

I had been suspecting it long before I found it. The name Read in the name of my ancestor, Reddin Read Bowden, was handed down to his descendants too, to his grandson Benjamin Read Richardson, and to Read Richardson’s daughter, Readie Ray Richardson—it wasn’t common for a first or middle name. And then I discovered that John Culpepper Bowden (b. 1813), son of Josiah Bowdoin, also had a son named Enoch Reid Bowden.

So the first time I found the name of Arthur Read (b. ca. 1748) of Randolph County, North Carolina in a shared match’s family tree, I knew there was something there. The match was clearly triangulated among descendants of Josiah Bowdoin. I searched the matches for the surname, and soon found others who were likewise triangulated. I had seen the name Spinks too in matches, but did not immediately realize the significance, even though I realized the Spinkses were also neighbors to the Bowdoins in Randolph County.

It was not until I joined the Randolph County Genealogical Society and gained access to the digital archive of their excellent Genealogical Journal that everything clicked almost all at once. I immediately discovered that Arthur Read had married Martha Spinks, the daughter of Enoch Spinks Sr. (d. 1772), and was an immediate neighbor to William Bowdoin (b. 1740) on the Deep River in Randolph County. This explained the presence of both the names Read and Spinks in a rapidly growing number of shared matches.

On a hunch, I suggested to my dad that we add (Unknown) Read as the mother of William Bowdoin (b. 1802), she the daughter of Arthur Read (b. ca. 1748) and Martha Spinks, and leverage ThruLines to discover other descendants of them in our matches. Within a day, in flowed 70 matches who were descended from Arthur Read, most of them well triangulated. Around 100 matches from Enoch Spinks appeared, though only about a third of them turned out to be valid (Spinks being at a greater ancestral distance and near the limits of autosomal matching).

I determined that the Read and Spinks were strongly triangulated with descendants of Josiah Bowdoin and William Bowdoin (b. 1802), and did not appear with any regularity with descendants of other children of William Bowdoin (b. 1740)―with one major exception: Martha Rebecca (Bowden) Maddox. When I still thought she was a descendant of James, I struggled to make sense of that. Discovering at around the same time that she was not a descendant of James and discovering Arthur Read and Martha Spinks instantly began to make sense of both.

| Match group (descendants of) | # who match at least one Read | Total Read matches | # who match at least one Spinks | Total Spinks matches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| William Bowdoin (b. 1802) | 64 (47.4%) | 533 | 12 (8.9%) | 30 |

| Eliza Bowdoin (b. 1817) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 | 3 (23.1%) | 3 |

| Martha Rebecca Bowden Maddox | 104 (81.9%) | 461 | 27 (21.3%) | 30 |

| Josiah Bowdoin (b. 1780) | 64 (61.0%) | 339 | 14 (13.3%) | 15 |

| Pleasant Bowden (b. 1785) | 10 (12.5%) | 10 | 3 (3.8%) | 3 |

| James Bowdoin (b. 1764) | 10 (12.5%) | 10 | 0 (0%) | 0 |

| John Bowdon (b. 1770) | 2 (13.3%) | 2 | 1 (6.7%) | 3 |

| Travis Bowdoin (b. 1772) | 9 (17.3%) | 13 | 1 (1.9%) | 1 |

| Elizabeth Bowdoin Macon (b. 1766) | 14 (37.8%) | 45 | 5 (13.5%) | 12 |

| Martha Bowdoin Odell (b. 1768) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 | 0 (0%) | 0 |

| Mary Bowdoin Macon (b. 1773) | 9 (30.0%) | 26 | 0 (0%) | 0 |

| William Bowdon (b. 1720) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 | 0 (0%) | 0 |

| Read | — | — | 27 (23.7%) | 59 |

| Spinks | 11 (78.6%) | 59 | — | — |

Conclusion

Close Read and Spinks matches are shared only with descendants of Josiah Bowdoin―with descendants of Enoch Bowdon (b. 1801) and John Culpepper Bowden (b. 1813), with William Bowdoin (b. 1801), and with Martha Rebecca Bowden (b. 1815). In the Read-Spinks matches, Martha Rebecca’s descendants have something exclusive in common with the other descendants of Josiah Bowdoin that no other group has. Martha Rebecca Bowden’s matches with each of the other group are of a strength, number, and character that can only mean she also was a daughter of Josiah Bowdoin and Ms. Read.

The theses that William Bowdoin (b. 1801)’s father was Josiah Bowdoin and that his mother was Ms. Read unite and form a whole. Matches from William’s group strongly indicate that Josiah was his ancestor, but only with the Read-Spinks matches are William’s descendants truly set apart and grouped with other descendants of Josiah and no one else. And it is only after we realize this connection, that the extent of the evidence that has always been there becomes evident:

| Descendant | Namesake |

|---|---|

| Enoch Bowdon (b. 1801) | Enoch Spinks |

| William T. Bowdon | Travis Bowdoin (perhaps?) |

| Henry Arthur Bowden | Arthur Read |

| Enoch Manson Bowdon | Enoch Spinks |

| Raleigh Bowdon | Raleigh Spinks |

| William Bowdoin (b. 1802) | William Bowdoin (b. 1740) |

| William A. Bowdoin | William Bowdoin (b. 1740, 1802) |

| Edward Read Bowdoin | Read family |

| James Arthur Bowdoin | Arthur Read |

| Isaac J. Bowdoin | Isaac Washington Read |

| Joseph Arthur Bowdoin | Arthur Read |

| Reddin Read Bowdoin | Read family |

| Sarah Emily Elizabeth Bowdoin | Emily Elizabeth Cooper |

| Benjamin Read Richardson | Read family |

| Readie Ray Richardson | Read family |

| John Culpepper Bowden (b. 1813) | Possible Culpepper connection to Spinks |

| Enoch Reid Bowden | Enoch Spinks, Read family |

| Raleigh Spinks Bowden | Raleigh Spinks |

| Martha Rebecca (Bowden) | Martha (Spinks) Read |

| Alfred Reed Maddox | Read family |

To me, the recurrence of the name Read in every branch, and the fact of such explicit names as Enoch Reid and Raleigh Spinks, removes any doubt that the mother of this family was a Read.

We do not know her name, but we are sure she existed. In online family trees, no one knows of a daughter of Arthur Read older than Amy (Read) Lawler (b. 1787)—but the 1790 and 1800 censuses both show that he had one.

Next steps

There is much more in the research paper than I could fit in this article. There is a lot more genealogy and a lot more Machine Learning. As for the Machine Learning, I think I will make at least one more post, so maybe this is a three-parter. 😊 Next time: Agglomerative Clustering!

Read the research paper this article is based on:

1 thought on “Connecting William Bowdoin, part 2: Finding answers through Machine Learning DNA Analysis”